|

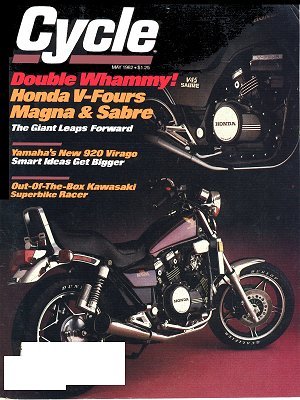

V45 Sabre Cycle Magazine, May 1982 |

|

|

HONDA |

Here's the great leap forward that Honda has been planning. Motorcycling after the Sabre will never be the same. The Sabre is a bargain at $3398, and it's the new standard of comparison. |

What constitutes A MILESTONE Motorcycle? First, it's

one that represents a departure, technologically and visually, from the

mainstream of things. Second, that departure must he broadly accepted. The bike

must take the industry and consumers by storm. Third, the motorcycle must be a

turning point rather than a technical or stylistic cul-de-sac. Its influence

should be felt and seen for five or ten years; if will most likely open a new

area which other manufacturers will be obliged to fill-though rarely with the

impact or completeness of the original. The milestone motorcycle may be a

styling exercise, a new displacement category, a new size, or a new design. Or

it may be a new everything. In that case, the motorcycle's significance is

obvious and overwhelming. The Honda VF750S Sabre is such a motorcycle.

The

Honda Sabre is one of the few truly new motorcycles of the past decade; its sum

of parts adds up to the most harmonious and creatively engineered package ever.

The liquid cooled V-four engine shows how manufacturers can comply with future

government environmental and safety standards, and still create a motorcycle

that delivers the performance and features enthusiasts demand. The Sabre is all

new; as such, it has an extraordinary capacity for further development.

Impressive as the V45 is now, Honda engineers have barely tapped its

potential. The

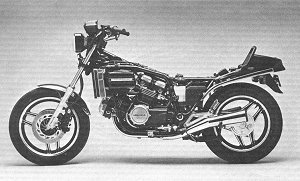

Sabre is the high-performance half of Honda's v45 pair, functionally far

superior to the Magna. Although both bikes share the 90 degree V tour, the Sabre

complements its engine with features and chassis performance the Magna does not

have.

The

Sabre is the high-performance half of Honda's v45 pair, functionally far

superior to the Magna. Although both bikes share the 90 degree V tour, the Sabre

complements its engine with features and chassis performance the Magna does not

have.

Looks aside, the most readily apparent difference between the two bikes

is riding position. The Sabre, with its relatively narrow handlebars and

highmounted footpegs, provides the rider with a well-braced platform from which

to carve high speed routes over his favorite twisting roads. Unlike the Magna,

the Sabre has Honda's Pro Link single shock rear suspension system. This

sharpens the Sabre's prowess as a backroad charger by offering progressive

springing by means of a linkage system and an air assisted coil spring, and

progressive damping with three way adjustable rebound control. Additionally, the

Pro Link system locates unsprung weight closer to the swing-arm axis,

an

important consideration when the bevel gears, drive shaft and sizable huh

inherent in shaft drive weigh down the tar end of the swing arm.

Other Sabre

exclusives include an electronic dashboard with LCD displays for fuel level and

coolant temperature. for the tripmeter, and for the combination stopwatch clock.

The turn signals are computerized and self-canceling. The Sabre and Magna ride

and handle as differently from one another as they look.

Sabre locomotion seems largely divorced from the principles of internal combustion as understood in motorcycling. The engine that is smooth and quiet. |

Great motorcycles are usually remembered for some

specific thing. Without doubt, the Sabre will be remembered for its engine. We

believe this V-four to be so significant that the engine itself was the subject

of a thorough technical analysis last month ("Honda V-Four," Cycle, April 1982).

While we'll not recap that technical elaboration here, some salient points

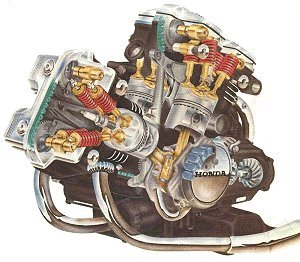

should be understood. The 90-degree V-four may well be the smoothest-running,

most vibration-tree motorcycle engine ever built. Only one other engine is as

free of vibration as the V45: Honda's GL1100 flat four.

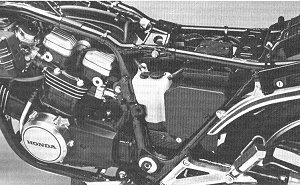

Other things make the

V45 unit compelling The V-four, with its common crankpin for each pair of

front/rear cylinders, is extremely narrow; its width is about the same as a mid

sized twin's. The narrow engine is located lower in the frame and lower to the

ground than an inline four can be. Moreover, the engine's center of gravity is

lower than the crank-shaft location might suggest, thanks mainly to the low

positioning of the V-four's forward bank of cylinders. Other important details:

Honda continues with four valves per cylinder, but the V45 uses an open-chamber

combustion chamber with a shallow Cosworth-type included valve angle of 38

degrees. Additionally, the V-four layout has allowed Honda to get very steep

induction tracts; that is, to get the intake port angle as close to the valve

stem angle as possible. It's a superior way to direct the incoming charge past

the valves. With an inline, transverse-mounted engine, necessary parts such as

fuel tanks and rider's knees restrict designers from tilting the carburetors to

an angle suitable to take advantage of steep-angle induction. With the Vee

layout, however, Honda can tip the intake tracts without invading the rider's

space.

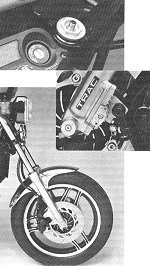

Air adjustable fork has valve under fork cap. Cover screws on the threaded valve which serves one tube. Spaceship control: LCD elements for fuel level and coolant temperature, time, trip-distance, stopwatch function; left side master cylinder is for master cylinder actuation; choke lever is bar mounted. Bars are a bit adjustable. Sabre has center axle 37mm fork, substantial fork brace, TRAC, twin piston calipers and dual discs. |

Traditionally, high-performance 75Ccc transverse

engines have lacked mid-range punch. These bikes have power surges around 6000

rpm. That's fine if the rider is willing to stir the gearbox to keep things

moving but what about the guy who wants to pass a line of cars or accelerate out

of a tight spot without banging away on the shift lever? For him there's the

Sabre.

Modern design allows excellent combustion chamber filling with

moderate valve timing. The result is an almost flat torque curve giving good

acceleration over a large rpm band; in this case 4000 to 10,000 rpm. Four grand

in sixth gear or overdrive, is right around 60 mph. Cruising-speed passing

rarely calls for a downshift.

With each succeeding engine generation,

maintenance chores are diminished. In the V45, the inverted-bucket tappet valve

system, with its selective shim valve-adjustment method common to the 750 and

900F series, has been replaced by the more practical finger type rocker-arm

cam-follower with its screw and-locknut adjustment method. The electronic

ignition has its timing preset and built in; no moving parts there. The oil

filter is now an external spin-on automotive type, and the silent-type camchains

are self-adjusting. Service-tree camchains need no external access, so the

tensioner hardware can be located inside the perimeter of the chain formed by

the crankshaft, intake and exhaust cam sprockets. Clutch adjustment is constant

with the new hydraulically actuated clutch. This also allows engine tensioners

to use heavy clutch springs without increasing lever-pull pressure. All that's

left of periodic servicing is to clean the foam air filters, change the oil and

oil filter and adjust the valves. Any of those service procedures can be handled

at home by someone with a few hand tools and a basic understanding of the

internal-combustion engine.

Crime fighter cable Stows in the tool box's upper tier.Security loop is made through cable-eye: male end plugs Into alarm anchor box on bike; only key can release cable If cable's fiber-optic link is broken alarm sounds. |

Honda engineers brought new technology to bear on the

V-fours to keep them light. While overall lightness was a major design

criterion, it was equally important to make the bikes strong and depend able.

Here's an example. Although high tensile, thin-wall tubing has been around for

quite some time, the special welding techniques it requires have prevented its

use in mass produced motorcycle frames. Honda's recent developments in

production technology, however, have allowed this strong lightweight material to

be used in highly automated assembly plants. This steel alloy weighs 16 percent

less than earlier frame pipes.

Road racing frame designers have long

understood the need for a sturdy chassis and the importance of tying the

steering head and swing arm pivot together as stoutly as possible. As engines

have become more powerful and tires supply more grip, frames have grown much

wider just behind the steering head, with the backbones splayed at wide angles

before straightening and heading back toward the swing arm area. This helps the

frame resist side-to-side twisting at the steering head, and is an important

step forward. All front line grand prix machines use such a

design.

This is about as much of the rear single shock as can be seen or reached on the Sabre. The air valve is a deep reach; best operating pressure was about 50psi. |

As street bike design moves rapidly ahead.

Manufacturers confront problems similar to those faced by race-bike designers.

The Sabre, a powerful motorcycle by 750 standards, has very wide tires. The

Sabre's frame shows grand prix influence. The backbone frame tubes are widely

spaced and well braced, much more so than any other current Honda road bike

we've seen. For a road bike, the Sabre is monstrously strong in the neck. The

rest of the chassis is a standard full cradle frame with a tube and box-section

swing arm.

The front suspension follows the 1982 Honda 750 Nighthawk by

having TRAC. Honda's anti-dive fork; the left slider has a tour position screw

slot selector by which the rider can choose a degree of anti-dive. TRAC, or

Torque Reactive Anti Dive Control, differs from Suzuki's and Yamaha's systems,

which are controlled via pressure in the hydraulic brake system. Instead, Honda

relies on the rotation of the left brake rotor to energize the anti-dive fork.

As the front brake is applied, the left caliper grips the rotor and rotates

forward, thus pushing a plunger and closing part of the compression damping

circuitry, effectively slowing fork dive during braking. The advantage of the

TRAC system lies in its mechanical activation: brake feel is completely

unaffected. (A full explanation of TRAC can be found in the Honda 750 Nighthawk

test in the April 1982 issue.)

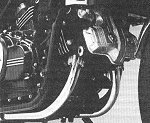

The subject of a thorough tech analysis

last month, Honda's V-four engine is a technically superior design, which

happens to be a functionally superior one,

too. The subject of a thorough tech analysis

last month, Honda's V-four engine is a technically superior design, which

happens to be a functionally superior one,

too. |

The Sabre fork has a feature not found on the CR750

Nighthawk: an integral fork brace tying the 37mm fork tubes together directly

above the chromed-steel front fender. This strengthens the front end assembly,

giving a positive feel to steering inputs with instant response at all times.

There are many reasons obvious and not so obvious for incorporating a brace into

the Sabre and Magna front ends, and we imagine Honda did so for all of

them.

A motorcycle fork is subjected to high-stress loads from all

directions. A head-on collision between the front tire and a sizable road

irregularity can bend fork tubes back toward the motorcycle, resulting in a

temporary misalignment of the fork, which creates diction. Braking also imposes

similar forces on the front end. Cornering loads push in all directions on the

tubes. Fast. Forceful steering inputs are another cause of temporary flex and

misalignment, with stiction and its companion. Slow fork response, instantly

appearing. These problems, common to all motorcycles, arise when bikes are

ridden hard in sporting fashion. On top of these, however, the Sabre has its own

special need for a fork brace.

The V-four has a very long wheelbase for a

sporting motorcycle; measuring 61.5 inches, it's 1.5 inches longer than that of

the stable handling CR750F. Long wheelbase motorcycles, because of chassis

dynamics, like to go straight, and offer considerable resistance to rapid

steering correction, especially if the motorcycle has ''conservative'' rake and

trail figures, which the Sabre does: 29.5 degrees of rake and 4.6 inches of

trail. This tends to amplify the twisting caused stiction when immediate

response is sought through fast steering input.

There is yet another Sabre

Magna exclusive. Both bikes are equipped with massive front tires, mounted on

rims 2.5 inches wide; this is much larger than the 1.85 inch rim that's the

front wheel norm for middle-to heavyweight bikes. The big rim and tire puts down

a large print, giving the tire more contact area and greater self-aligning

torque than the norm.

Initial riding impressions taken from different riders

hot off the Sabre's seat were of a motorcycle with a medium to-long wheelbase

and fairly steep geometry of about 28 degrees rake and four inches trail. The

bike felt stable at high speed, but it steered fairly lightly - sensations in

accord with our speculations about the bike's geometry. The Sabre's long

wheelbase for a 750 and its Ducati-esque rake and trail surprised us. Figures on

paper suggest that the Sabre would steer like a lumber truck, providing

straight-line locomotive stability at the expense of quick and accurate

steering. But the Sabre is, in fact, delightful to ride in a sporting

environment, or anywhere.

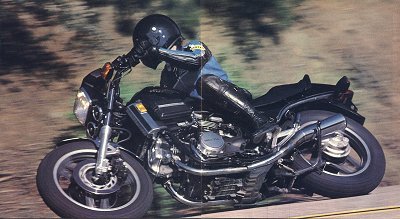

The Sabre practically begs to be ridden hard. The

engine is deceptively smooth, propelling the bike down the road with such

apparent ease that, through the test period, riders were amazed to see the

speedometer at 86 mph when they expected 66 mph. More than one staffer was

shocked to see the gear indicator showing fourth after two or three miles on the

freeway. The Sabre is that smooth. Riding at 76 mph with ear plugs

produces an eerie feeling; the engine - neither audible nor vibrating - seems to

melt away and disappear. The rider feels as if he's floating down the road,

detached from internal combustion. Only shocks transmitted through the

suspension tell the rider's non-visual senses he's actually on the ground moving

forward. The engine's smoothness makes highway travel seem absolutely

effortless. The Sabre will cruise at any speed, including those off the speedo

face, without a buzz.

Initial rides aboard the Sabre brought many Comments

about the clutch. The V45's hydraulic clutch has a less linear engagement than

conventional cable-and-linkage operated clutches. Initial engagement of the

hydraulically actuated clutch is sudden; it can catch the uninitiated unaware.

After a short familiarization, however, riders' clutch complaints all but

disappeared.

Around town the new Honda is pleasant to ride, a result of its

crisp, clean carburetion. There are none of the EPA-inspired coughs or stutters

from the engine to catch the rider off guard and cause an anxious moment during

low-speed maneuvers. The seat gives the impression of being considerably lower

than its 30.7 inches. Because it slopes down at the sides considerably, our

five-eight rider could easily put both feet flat on the ground at a stop. The

steering is light, and the motorcycle shows no tendency to "turn in" at parking

lot speeds.

Open roads bring out both good and had qualities of a

motorcycle's seat and riding position; here the Sabre suffers somewhat. The low

seat height, though welcomed by short riders, creates a double problem for the

long distance rider. To keep the seat low, Honda gave the seal a well defined

pocket for the pilot, and then cut the foam padding between the seat base and

seat cover quite thin. These design elements treat the long distance rider

rudely. The rider pocket commands: Sit Here. Then the thin under padding

compresses to the point of bottoming out, leaving the rider's but locks burning

in pain inside 90 minutes, and the rider can't move to stop the pain. Okay, low

seals are nice, but a rider should be able to hold a motorcycle up safely

without both feet flat on the ground and his two legs planted like landing

struts. After all, the rider spends more time sitting on the motorcycle while in

motion than he does balancing at a stop. The highway ride of the air-assisted suspension brings out the "sport"

characteristics built into the Sabre. Suggested fork air pressure falls between

six and 14 psi. Highway riding calls for compliance, so we set the fork air

pressure at eight psi, the rear shock at 40 psi and adjusted the shock's rebound

damping lever to position one, which offered the least damping. At these

settings, with a 150 pound rider aboard, the ride was rather firm, but usually

not bothersome. Freeway expansion joints exposed the Pro Link's shortcoming.

Over the joints it's jolt city. Lower pressures proved to be no solution; they

only caused frequent bottoming over medium-sized bumps.

The highway ride of the air-assisted suspension brings out the "sport"

characteristics built into the Sabre. Suggested fork air pressure falls between

six and 14 psi. Highway riding calls for compliance, so we set the fork air

pressure at eight psi, the rear shock at 40 psi and adjusted the shock's rebound

damping lever to position one, which offered the least damping. At these

settings, with a 150 pound rider aboard, the ride was rather firm, but usually

not bothersome. Freeway expansion joints exposed the Pro Link's shortcoming.

Over the joints it's jolt city. Lower pressures proved to be no solution; they

only caused frequent bottoming over medium-sized bumps.

Sport riding calls

for firmer adjustments. We raised fork pressure to 12 psi, rear shock pressure

to 50 psi and the damper lever to the full-boogie level, number three. This

setup made the Sabre very stable and precise, but the front end was unacceptably

harsh. Dropping the fork pressure to 10 psi improved the ride somewhat. We

continued our search for decent fork compliance in the sporting mode and lowered

the fork air pressure even further, down to our touring-tested eight pounds. At

eight pounds, fork action became acceptable except for frequent bottoming, which

is a major exception. That's no good. Why could Honda's 750F series offer a

decent ride for sport-riding without any bottoming? Honda claims a fork travel figure tar the Sabre of 5.5 inches,

considerably less than the F's 6.3 inches. That's a partial explanation, but

there's more. Our Sabre never gave mare than 4.75 inches at actual travel in any

kind at riding we did. At a pressure at eight psi the fork would sag two inches

with a 150-pound rider aboard. That makes 2.75 inches at usable fork compression

when touring down a smooth road. In these days at compliant, long-travel

suspensions, this is a serious compromise in order to get two feet flat on the

ground at a stop.

Honda claims a fork travel figure tar the Sabre of 5.5 inches,

considerably less than the F's 6.3 inches. That's a partial explanation, but

there's more. Our Sabre never gave mare than 4.75 inches at actual travel in any

kind at riding we did. At a pressure at eight psi the fork would sag two inches

with a 150-pound rider aboard. That makes 2.75 inches at usable fork compression

when touring down a smooth road. In these days at compliant, long-travel

suspensions, this is a serious compromise in order to get two feet flat on the

ground at a stop.

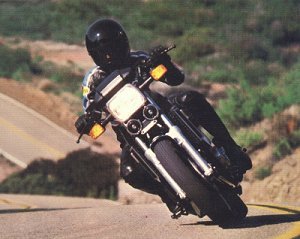

Suspension travel limitations aside, the Sabre's backroad

performance is extremely creditable indeed, especially considering it has shaft

drive. The combination of wide rims and tires, the integral fork brace, TRAC,

excellent ground clearance and the narrow and smooth V-tour engine works to form

a motorcycle that can be ridden harder and with less fatigue than the majority

of sport bikes. If we were trying to make time in a 200-mile run, we'd take the

Sabre.

Many bikes with shaft drive require special riding techniques to

extract full sporting potential. Because shaft bikes fall on - or compress -

their suspension when the throttle is closed, cornering clearance can be

fleeting. Proper high-performance riding on shafties dictates that the rider

finish braking somewhat early so he can roll on a bit of throttle early enough

to get the bike up off its haunches. Because the Sabre has such generous ground

clearance, this technique becomes largely unnecessary, even when rushing along

in the biggest at hurries. The footpegs rarely touch down, and must be folded

considerably before anything solid will touch down. With the suspension

compressed about 65 per-cent, the Sabre still offers a lean angle of some 43

degrees. These limits are well beyond what is prudent.

The Sabre shows that

Honda already has one technological foot firmly into tomorrow. Honda's

willingness and ability to play by current rules while engineering into the

future, anticipating new rules, is encouraging. The Sabre sets many new

standards in production motorcycle design and technology, and the motorcycle

says Honda is moving ahead, full at ideas, and there is no end in sight to the

continued production and sale at technologically enlightening

motorcycles.

Granted, the Sabre is not perfect. Chief complaints center

around the suspension's short travel and consequent performance, and the seat's

poor comfort qualities over the long haul. These problems might go by relatively

unnoticed on a rehashed version of a UJM. However, the Sabre is so substantially

superior to UJMs in so many areas that unsolved problems or annoyances assume

the importance - though not the proportions - of major faults.

The Sabre has

given us more cause for praise than any new motorcycle since the introduction of

the 750cc Ducati V twin in 1972. Its faults are few, and in time Honda will most

likely smooth, hone and polish the rough edges. Even our resident chronic

complainer came back bubbling with delight after a lengthy Sabre excursion, and

he's normally as effervescent as vinegar.

With the Sabre, the curtain to the

future has been raised. For those of you who thought motorcycling would repeat

itself info a tasteless and homogenized future, you can stop moping now and

rejoice. The Honda Sabre says the future of street motorcycling is as bright and

incandescent as we've ever seen it.